|

|||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

|

Algae Sand Intertidal animals Intertidal crustaceans Tide-pool birds |

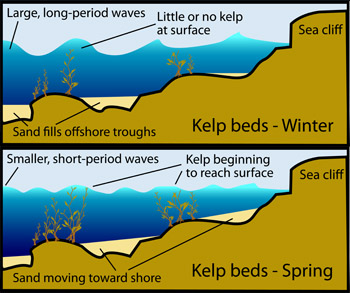

Algae recolonize intertidal rocks By April, the tide pools are starting to look less battered than they did earlier in spring. Annual red and green algae begin to colonize bare spots while brown algae begin to regrow from their tattered holdfasts and stipes. Many of the annual seaweeds that germinated from spores early in spring are growing rapidly, and are only occasionally damaged by late winter storms. During their spring growth spurt, these annual red and green algae out-compete the perennial brown algae, at least for a month or two. All this new algae provides plenty of food for snails, limpets, and other grazing animals in the tide pools. During April, conditions in Central Coast tide pools can change even more dramatically than at other times of year. At low tide, spring sunshine can warm the water a tide pool until it reaches over 80 degrees Fahrenheit. But when the tide rises, the pool may be filled with water from an upwelling event that may be 30 degrees colder. Late rains may turn the tide pools brackish, but increasing sunlight can evaporate the water, making the pools extremely salty. Sand moves from the kelp beds toward shore  These diagrams show some of the ways that conditions in the kelp beds change as winter progresses into spring time. (Source: Kim Fulton-Bennett) In April, the smaller intertidal algae run a serious risk of being buried by sand. As winter storm swells give way to the smaller wind-driven waves of spring, sand gradually moves from the kelp beds in toward shore. In protected areas, this sand may begin to rebuild winter-ravaged beaches. Along exposed coastal areas, however, late storm waves and short-period wind waves keep this sand from reaching the shore. Instead, the sand spends a lot of time shifting around between the kelp beds and the beach, smothering intertidal areas in a layer of abrasive particles that can be several feet thick. In the rocky intertidal areas just north of Monterey Bay, this transient intertidal sand layer reaches its maximum thickness in April or May. By July or August, most of this sand will have reached the shore, building up pocket beaches, and leaving the intertidal rocks exposed once again. Note: The movement of sand toward shore in spring and summer is a slow, intermittent process, which may take three to six months. However, the reverse process--the movement of sand from the pocket beaches out toward the kelp beds by storm waves--can take place in a matter of days or even hours. During April, as the sand moves into intertidal areas, it buries everything in its path, including intertidal algae and attached animals. Thus, differences in sand movement from one tide-pool area to another affect that types of algae and animals that live each area. As sand begins to fill in low areas and intertidal surge channels, mobile animals, such as black turban snails, migrate away from these areas. Other animals, such as many limpets and chitons, can't run away because they can't crawl over sand. They also can't crawl up to the upper surfaces of rocks or they will be easy pickings for shore birds. Thus, these animals must stay put on their rocks and try to survive being buried by the shifting sands. Most tide-pool animals will suffocate if buried under sand for more than a few days. For example, Colisella scabra, a common intertidal limpet, can survive being buried under an inch of sand for up to five days. Similarly, mossy chitons (Mopalia mucosa) can survive a week or two buried beneath the sand. Phragmatopoma tubeworms are also well adapted to being buried alive. These colonial worms live inside tubes that they build from grains of sand. Once you know what to look for, you can't miss their bulbous, brown colonies, which look somewhat like wasps nests enveloping the vertical sides of rock ledges. Of course, in the ultra-competitive environment of the tide pools, there are a few animals that can survive weeks or even months of burial under several feet of sand. These hardy survivors include the proliferating anemones (Anthopleura eligantissima) and some annual algae, such as Polysiphonia and Graclariopsis. In fact, some deeper intertidal red algae go dormant during spring and summer, when they are most likely to be covered with sand. They do most of their growing during fall (when the sand is on the beaches) and during winter (when the sand is out near the kelp beds). Intertidal animals (turban snails, black limpets, lined chitons, ochre sea stars) begin spawning Perhaps because of the abundance of young, tender algae in spring, many grazing animals of the tide pools give birth at this time of year. For example, two of the most common mollusks of the high intertidal rocks, turban snails and lined chitons, lay their eggs at this time of year. Also in April, females of several small, intertidal crustaceans (amphipods, isopods, and copepods) can be seen carrying broods of eggs. Note: April is just the beginning of the spawning season for intertidal animals. As spring moves toward summer, more and more tide-pool animals will be laying eggs, brooding eggs, or releasing larvae. Turban snails lay eggs  Three turban snails, one with a black limpet attached to its back. (Source: Kim Fulton-Bennett) If you peer into almost any tide pool on the Central Coast, you are likely to see black turban snails (Tegula funebralis) gathered near the bottom of the pool. If you look closely during April, you may also find the turban snails' newly laid eggs, which look like tangled strings of overcooked ramen noodles, Each string contains several hundred eggs. About a week after they are laid, the turban snail eggs begin to hatch, releasing microscopic larvae that drift with the coastal currents for about five days. This short drifting period reduces the chance that the larvae will be swept out to sea, and increases the chance that they will settle near the tide pool in which their parents lived. After five days, the swimming larvae settle onto the seafloor. You may see these tiny, young turban snails crawling around the lower intertidal rocks. They eat microscopic algae, which are abundant in spring on rock surfaces that have been scraped clean by winter storms. As these young turban snails grow larger, they will move up to the higher tide pools and feed on larger algae. Adult black turban snails gather in crevices and deeper tide pools at low tide and emerge to feed as the tide rises (but only if the waves aren't too rough). One reason that black turban snails are so numerous is that they can eat all sorts of different algae--everything from thin films of diatoms to fragments of drifting kelp and red algae. The turban snails, in turn, provide a year-round supply of food for sea stars, anemones, crabs, sea otters... and humans. If not eaten by a predator, however, turban snails can live for a surprisingly long time--up to 20 or 30 years. Black limpets (on turban snails) lay eggs If you pick up a few turban snails, you may see little black bumps on their shell. These are black limpets (Collisella asmi), and they live only on turban-snail shells. Competition for hard surfaces is fierce in the tide pools. Even small, mobile animals such as a turban snail may serve as a "substrate"--a surface on which other animals attach and live. Growing just a little over a quarter inch across, black limpets eat microscopic algae that grow on turban snail shells. However, each turban snail only provides a small growing ground for algae, so black limpets must change hosts each day. They usually do this at low tide, when the turban snails are huddled together in the deeper tide pools. Like their hosts, the black limpets reproduce in spring. However, they apparently have a second reproductive period in fall, just in case. Lined chitons spawn Another common tide pool denizen and April spawner is the lined chiton [Tonicella lineata). Many other species of chiton spawn a little later, in May or June. Note: Lined chitons spawn one to two months later in Washington state than they do in Central California. Unlike many tide pool animals, which release hundreds or thousands of eggs, female lined chitons release just two to three eggs in each cluster (though a single chiton may give birth multiple times in a single year). These eggs are fertilized by male chitons, which release sperm at the same time. The fertilized chiton eggs hatch after about two days, releasing larvae. Like the turban snail larvae, these chiton larvae drift in the water for about a week, getting nutrition from tiny yolk sacs. Like the larvae of abalone, rock crabs, and many other intertidal animals, the larvae of lined chitons prefer to settle on or near coralline red algae. In fact, the chiton larvae require some chemical in coralline red algae to finish their development process. This process takes about a month, during which the larvae cannot eat, but continue to live off their yolk sac. Only at the end of the month do the young chitons begin feeding on the coralline red algae on which they settled. Like newly settled turban snails, young lined chitons hang out in lower intertidal areas, then gradually move higher up as they mature. Also like the turban snails, adult lined chitons typically hunker down under a home rock at low tide, then come out to graze at high tide. Unlike turban snails, adult lined chitons are picky eaters. They feed only on red coralline algae. Most lined chitons spend their entire lives around the coralline algae that form hard pink crusts on intertidal rocks. The chitons incorporate pigments from the red algae into their bodies, turning them pink and allowing them to blend in with the algae. Looking at a crusty red patch of coralline algae, you might wonder how any animal could eat that stuff. It turns out that lined chitons have just the right tool for the job. Like most snails and chitons, lined chitons eat algae with their radula, which looks like a cross between a tongue and a steel file. In fact, the radula of a lined chiton actually contains tiny bits of magnetite--a very hard mineral that is mostly iron. Having this hard, rocklike material inside their bodies may also make lined chitons less palatable to predators. In any case, they are generally avoided by sea stars, one of the primary predators in the tide pools. Ochre sea stars spawn Speaking of sea stars, grazers aren't the only tide-pool animals that spawn in April. One of the most voracious tide-pool predators, the ochre sea star (Pisaster ocheracous) also spawns at this time of year. During April or May, ochre sea stars release their eggs and sperm into the water. Note: Ochre sea stars in Puget Sound spawn a month or two later, from May through August. The fertilized sea-star eggs develop into free-swimming larvae that spend several months at sea. Most of these larvae will settle onto the seafloor in June or July, when there are plenty of young snails and mussels for them to eat. If you see a large sea star in a Central Coast tide pool, chances are it's an ochre star. Despite their name, ochre sea stars can be yellow, orange, brown, red, or even purple in color. At low tide, ochre sea stars hang out just below mussel beds or colonies of goose-neck barnacles. At high tide, they move up into these colonies and begin feeding. Watching an ochre sea star feed is like watching a B-grade horror movie in slow motion. After wrapping its five arms around some unlucky mussel, the sea start pulls its shell open just a little (even 1/100 of an inch is enough). The sea star then inserts its stomach through the gap between the shells. The stomach releases enzymes and acids that digest its prey inside its own shell. Talk about nasty ways to die... Although they favor mussels and barnacles, ochre sea stars will eat almost any animal that they can get their stomachs around, including chitons (except lined chitons), limpets, and turban snails. Many snails and other slow-moving tide-pool animals get into high gear and boogie away if they sense an ochre sea star entering their tide pool. Like the monsters in some horror movies, ochre sea stars are practically indestructible, despite the best efforts of desperate sea otters, sea gulls, and young boys. If something tears off a sea star's arm, the arm will grow back in a month or two. Sometimes the severed arm itself will grow into a new sea star. Ochre stars can survive without eating for as long as two years. They can also survive out of water for quite a while. Like the Wicked Witch of the West in the Wizard of Oz, one of the few things that makes an ochre sea star uncomfortable is being bathed in warm, fresh water. Starting in about 2013, many of these fearsome predators succumbed to a strange disease called "sea-star wasting disease," which caused them to become soft and squishy, as if they were melting. Fortunately, not all ocher sea stars perished during this epidemic, and by 2017, they were beginning to recover along some parts of the California coast. Intertidal crustaceans (isopods, copepods) bear eggs If you happen to be clambering around Central Coast tide pools at twilight, you may come upon groups of multi-legged creatures that resemble (and are in fact relatives of) the "pill bugs" in your garden. These are intertidal isopods, otherwise known as "rock lice." If you are really adventurous, and are able to catch one of these wriggling creatures, you may find that it is carrying a cluster of eggs next to its belly. Several local species of rock lice brood their eggs from March through June. Western rock lice carry eggs  Western rock louse (about 1.25-inch long). (Source: Kim Fulton-Bennett) The western rock louse (Ligia occidentalis) lives in areas that are only wetted by the highest of tides. These animals are only partially adapted to life in the ocean. They breathe through gills, but they will drown if held underwater. In order to keep its gills moist, a western rock louse must periodically descend to the water's edge. After testing the water in a tide pool with its antennae, the rock louse dips its tail into the pool and soaks water up into its gills to keep them moist. In their efforts to stay damp but not wet, western rock lice hide under rocks and seaweed during the daytime. They emerge in late afternoon and spend their evenings scavenging for bits of seaweed and dead animals or scraping microscopic algae off intertidal rocks. Cirolana isopods carry eggs Cirolana harfordi is another intertidal isopod that you may find carrying eggs in April. Each female Cirolana isopod produces one or two broods of eggs a year, with each brood containing up to several dozen eggs. Just as you can often find pill bugs in a garden by turning over a rock, so you can find Cirolana isopods by turning over mid-intertidal rocks (or poking around mussel beds). Cirolana isopods can occasionally be found in huge groups. One marine biologist observed tide pools near Carmel that contained over 12,000 isopods per square yard. Like the pill bugs in your garden, Cirolana isopods are mostly scavengers that feed on dead animals and debris. When hungry, they will also catch and eat small worms, beach hoppers, and intertidal copepods. Cirolana isopods, in turn, provide a reliable, year-round source of food for perch and kelpfish. Tide-pool copepods carry eggs In addition to the isopods mentioned above, a unique species of tide-pool copepod also carries eggs in April. Although large compared with its relatives in the open ocean, Tigriopus californicus is barely visible to the naked eye. But if you know what you are looking for, these tide-pool dwellers are relatively easy to find. Go out on a sunny day and search for a tide pool high up on the rocks, where only the very highest tides can reach. The tide pool may at first appear barren and lifeless. But look closely at the bottom of the pool and you may see hundreds of tiny red "bugs" swimming around in the warm, stagnant water. These are copepods in the genus Tigriopus. If you collect some of these tiny copepods in April and look at them under a strong magnifying glass or microscope, you will see that some of them are carrying eggs. Once they colonize a particular tidepool, they reproduce rapidly, taking advantage of the habitat before the water evaporates or is swept out of the pool during a particularly high tide. Tigriopus copepods live off of tiny bits of organic debris that settle on the floor of their tide pools. They must be extremely hardy to survive in the highest tide pools, where the water can change from a sun-warmed 80 degrees to a chilly 50 degrees with the splash of a single wave. They must also survive when rain or solar evaporation causes dramatic changes in the salinity of their tide pools. Tide-pool birds (turnstones and surfbirds) congregate before leaving the area to nest While you are poking around the tide pools at dawn or dusk, you may see flocks of grayish, robin-sized birds also poking around. These are likely to be black turnstones or surfbirds. Both birds spend their winters on the Central Coast. In April, they gather in large flocks and begin to migrate northward to the far reaches of Alaska and Canada. They will spend the summer mating and nesting in the Arctic. Black turnstones congregate and migrate From October through March, you can often see small flocks of black turnstones (Arenaria melancephala) stalking in the tide pools, tossing aside bits of seaweed to get at the small animals (such as isopods) hiding underneath, In April, however, you may see groups of hundreds or even thousands of turnstones passing through during their northerly migration. Each day, the migrating turnstones fly rapidly northward along the coast. At nightfall, they stop to rest. Twilight is a good time to look for these flocks of tired turnstones landing on rock ledges along the Central Coast. Like long-distance drivers, they will stop for a quick bite to eat (look out, sea lice!), then turn in for the night. By the end of April, most of these turnstones will have arrived at Prince William Sound, in Southern Alaska. There they will stop and rest before continuing north. By early May, the birds will have reached their primary nesting area--the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in Western Alaska. This immense river delta serves as a nesting area for about 80% of all the turnstones from the west coast of North America. The little shore birds will gather in huge numbers on wet, grassy meadows that are just greening with the spring thaw. The turnstones will gorge on insects and perform intricate courtship dances, both on the ground and in the air. By late May or early June mated pairs will have built nests and laid their eggs. Racing to keep up with the short Alaskan summer, the nesting turnstones will incubate their eggs for just over three weeks. During this time, the parents must aggressively defend their nests. Although turnstones are nearly silent when foraging along the coast, one researcher described how nesting turnstones chased away ravens and other aerial predators with "shrieking vocalizations and strong, relentless pursuit, often resulting in bodily contact or pulling of feathers." Pretty impressive for a bird that is a little smaller than a robin. If not eaten by predators, the turnstone eggs will hatch in late June or early July. The adults and newly fledged birds will return to the Central Coast in fall. Surfbirds congregate and migrate Like black turnstones, surfbirds (Aphriza virgata) spend their winters around Central Coast tide pools, then head north in April. But surfbirds have an even more strenuous migration. Starting in early March, flocks of surfbirds leave the Gulf of California and begin migrating up the West Coast, their numbers growing as they move northward. This wave of migrating surfbirds typically passes over the Central Coast some time in April. By late April or early May, the wave of surfbirds will have reached Prince William Sound, in Southern Alaska. After a brief stop to refuel, the surfbirds will head inland, far from the sound of the breaking surf. During the final leg of their journey, the little surfbirds will fly hundreds of miles inland and thousands of feet up, into the remote mountain ranges of Alaska and western Canada. By late May, most of them have begun building nests on steep, rocky slopes and ridges amidst scattered tundra (the only vegetation that can survive in this harsh environment). Note: Although surfbirds spend half of the year within a few feet of the water's edge, they nest on talus slopes more than 4,000 feet above sea level. Like their cousins the black turnstones, surfbirds become uncharacteristically demonstrative when courting and mating. Courting birds flutter upward hundreds of feet above the mountain ridges, then glide through the air in long sweeping arcs, emitting high pitched squeaks, screeches, and chirrs. Mated females lay eggs from mid-May to early July. The males then incubate the eggs for about three weeks. The male surfbirds also feed and care for the young, occasionally leaving the nest to sprint across the rugged mountain slopes, chasing insects that it feeds to its young. Like the turnstones, surfbirds will return to Central Coast tide pools in fall. |