|

|||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

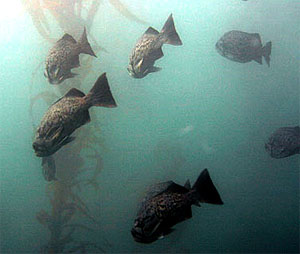

The kelp canopy is thin or nonexistent in many areas  Kelp holdfast that has been torn loose by storm waves. (Source: Claire Fackler, NOAA) January and February are probably the toughest time of the year for Central Coast kelp beds. Since November, winter storms have brought southeasterly winds and storms waves. Depending on how severe the winter storms have been, by January or February the kelp canopy (the part of the kelp you can see at the surface) may only show a few remnants, or may be gone entirely. Even kelp beds in protected areas are likely to have just a few spots of canopy, rather than extensive areas, as in summer. Earlier winter storms sometimes remove the blades of giant kelp, leaving just the floats. This actually protects the kelp to some extent, by reducing its drag, while the remaining floats help keep the rest of the plant upright so that blades below the surface can continue to receive sunlight. Repeated periods of large storm waves tear off floats, break the kelp stipes (stalks), and occasionally pull entire kelp plants off of their rocky bases. The condition of giant-kelp beds in January and February depends on how many severe storms have hit the Central Coast during the previous months. During typical years, the kelp canopy (the part of the kelp visible at the surface) has been reduced to tattered remnants a few feet across. During mild winters, on the other hand, the kelp canopy may look “moth-eaten,” but patches five to fifteen feet may still be common, and new blades may continue growing in all winter. During stormy years, you may see little or no kelp canopy (the part of the kelp that is visible at the surface) even at low tide. You may still see a “slick” at the sea surface, which indicates where kelp plants are growing below the surface, but have had their upper reaches “pruned” by winter storms. Even below the surface, the kelp plants may be reduced to bare stipes and a few floats, since many of the blades have been removed by wave turbulence. However, these remaining stipes and floats present very little resistance to wave action, and thus allow the plant as a whole to resist the waves. Even though the kelp canopy may be decimated, battered kelp stipes and blades can still be found ten or twenty feet below surface. Similarly, most kelp “holdfasts” (the part of the plant that is attached to the seafloor) will survive. Between storms, if the ocean calms down and the sun comes out for a week or so, the surviving holdfasts will begin to send new stipes up toward the surface. During much of the winter, any new growth is usually limited by lack of sunlight (low sun angle) and wave damage during storms. Many of the snails, crabs, bryozoans, and other small invertebrates that colonize the kelp canopy during summer leave the canopy during the winter months or are removed, along with the kelp itself, during winter storms. A few of these animals hide among the kelp holdfasts. Others head into deeper water . Kelp rafts form floating oases  California sea lion next to a raft of floating bull kelp. (Source: Jennifer Stock, NOAA) If you're out in a boat in Central Coast waters during January or February, chances are you'll see an often overlooked source of both food and shelter--rafts of drift kelp. Formed from masses of interwoven kelp plants that have been uprooted by winter storm waves, such rafts may drift for weeks, and end up dozens of miles from shore. They often mark the locations of ocean “fronts”--the boundaries between different water masses. Such areas are hunting grounds for seabirds, marine mammals, and large fish. Each kelp raft is a microcosm. A floating island. Rafts may shelter a variety of animals. Some of these, like kelp crabs or snails, lived on the kelp when it was growing near shore. Other kelp-raft residents include open-ocean fish, such as young rockfish, which find the drifting kelp a handy shelter from larger fish and seabirds. Both seabirds and large fish sometimes follow kelp rafts, picking off those smaller animals sheltering in the canopy. Bull kelp begins to die off Outside of Monterey Bay, in the more exposed portions of the Central Coast, the kelp beds are made up of bull kelp (Nereocystis luetkeana) rather than the more familiar giant kelp. Such bull-kelp beds are typically found on exposed, west-facing beaches, where they are exposed not only to southeasterly winds, but also to the full force of winter swells from the Gulf of Alaska that can be up to 20 feet high. Unlike giant kelp, which has a thin, branching stipe (or stalk), bull kelp has a single long stipe that grows to 60 feet long and tapers like bull whip. At the upper end is a hollow float the size and shape of a small bowling ball. Leaf-like blades grow out of the top of the float like a “mohawk” haircut. Bull kelp plants typically germinate in spring and live only 12 to 18 months. Toward the end of their first year, the oldest plants are often heavily laden with hitchhiking red and green algae. These hitchhikers add drag and make these bull kelp more likely to be broken off by winter storm waves. Younger bull kelp plants simply shed their blades under storm conditions, which reduces the drag of the waves and reduces the chance that the entire plant will be yanked up off the seafloor. Understory algae receive sunlight and begin to grow In January and February, the seafloor underneath the kelp may be relatively barren. The deeper “surge channels” between kelp beds may be filled with sand that has been stripped from nearby beaches by winter storm waves, then deposited offshore. By January, the leafy red algae that grow in abundance underneath the kelp canopy during summer have pretty much died back, been ripped out by storm surf, or been buried by shifting sand. Murky water and wave scour usually prevent new algae from growing up in sand channels during winter. However, on exposed rocky reefs, the ultra-hardy coralline red algae put on their year’s growth during the winter months, when the kelp canopy is thin and tattered, resulting in more light reaching the sea floor. By the end of February, the kelp canopy is at its thinnest. Shafts of sunlight illuminate parts of the seafloor that do not get direct light at any other time of year (because they are shaded by the kelp canopy). In response to this sunlight (along with increasing day lengths and the nutrients from early upwelling events) some leafy red algae begin their annual spring growth spurt. These algae also benefit from the fact that relatively few grazing and encrusting animals are present. In wave-protected areas such at Hopkins Marine Lab, microscopic young red algae on the seafloor may begin to sprout from spores in February. Many of these are annual species whose parents were buried by sand or torn out by storm waves during the previous winter. In more exposed locations, such as Lighthouse Point, near Santa Cruz, sand scour keeps such "understory algae" from growing back until wave conditions settle down later in spring. This process will accelerate in March. Winter-spawning rockfish release young  A school of blue rockfish swim around a kelp stipe. (Source: Chad King, NOAA/SIMON) Just as some deep-sea rockfish release their young in January and February, so do several species of kelp-bed rockfish, including blue rockfish and black rockfish. Blue rockfish (Sebastes mystinis) are one of the most common rockfish of Central Coast kelp beds, and typically give birth to live young in mid January. Blue rockfish mate in October, but the female blue rockfish stores the male's sperm inside her body until December. At that point the hundreds of thousands of eggs are fertilized and begin to develop. The blue-rockfish larvae that are released as live young in January will drift and swim near the surface of the open ocean for the next four to five months. During this time, they will eat the drifting eggs and larvae of other animals. One of their main food items are young copepods, which hatch during several waves as the spring progresses. By April or May, the blue rockfish larvae will have developed into juveniles (which look more or less like small adults). At this point they will return to the kelp beds, sometimes gathering in large schools. Spring-spawning rockfish mate Not all rockfish release young in winter. In addition to the many "winter-spawning rockfish," a second group of rockfish follows a later schedule, giving birth in late spring. The "spring spawners in the kelp beds include kelp rockfish, gopher rockfish, and black-and-yellow rockfish, all of which mate in late January or February. Gopher and black-and-yellow rockfish will release their young between March and May. Kelp rockfish wait even longer, and release their young in May or June. If you compare the winter-spawning and spring-spawning rockfish, it's interesting to note that the transition months are similar, even if the life stages during those months are different: Winter-spawning rockfish:

Spring-spawning rockfish:

Young predatory kelp-bed fish (greenling, cabezon, and lingcod) hatch from eggs As winter-spawning rockfish larvae are being released from their mother's bellies in January and February, other young kelp-bed fish are hatching out of eggs laid on the seafloor. These early-hatching fish, greenling, lingcod, and cabezon, are all predators. They lay sticky masses of eggs on the seafloor in October or November. After the eggs hatch, the larvae of these predatory fish spend relatively little time in the plankton and grow rapidly. This ensures that, when the young fish return to the kelp beds, they will be large enough so that they can catch and eat smaller fish that are returning at the same time or slightly later in spring.  A female kelp greenling lurks near the seafloor. (Source: Steve Lonhart, NOAA/SIMON) The eggs of Kelp greenling (Hexagrammos decagrammus) begin to hatch in late December or early January, releasing tiny transparent larvae that are 1/3 of a inch long. Greenling larvae have large yolk sacs, which allow them to grow and develop even if they don't find much food during their first few days drifting in the plankton. The larvae grow rapidly and within a week or so, begin to gobble up fish eggs or smaller fish larvae that drift past. By March, the young greenling will be two to three inches long, and will return toward shore to colonize the kelp beds. The eggs of another formidable kelp-bed predator (and relative of kelp greenling), the lingcod (Ophiodon elongatus) also hatch in January or February. Lingcod lay their eggs in shallow rocky areas in October or November. After the eggs hatch, the 1/4-inch-long larvae that spend about ten days hanging out near the seafloor and living off of their yolk sacs. When the "bag lunch" of their yolks is all used up, the lingcod larvae rise up toward the ocean surface and drift around in the ocean for several months. During this time, they fatten up on copepods and their eggs, as well as amphipods, crab larvae, and young krill. Sometimes they drift into estuaries and stay there until they become juveniles. Like the greenling larvae, lingcod larvae begin moving back toward shore In March, when they are two to three inches long. They will settle back down to the nearshore seafloor in May or June.  Cabezon on seafloor. (Source: John Ugoretz, California Department of Fish and Game)  Cabezon eggs surrounded by California hydrocoral (Stylaster californicus) and strawberry anemones(Corynactis californica). (Source: John Ugoretz, California Department of Fish and Game) Cabezon (Scorpaenichthys marmoratus) eggs also begin to hatch in late January. These eggs are laid in seafloor nests dug out by the male cabezon. Throughout the winter storms, the males guard these eggs and keep them clean. Once the cabezon eggs hatch, tiny, transparent larvae are released to drift with the nearshore currents until April or May. During this time, they eating copepods and other drifting larvae, including others of their own kind. |